Sermon given by Padre Richard Hall - Sunday 22 Apr 2012

Sermon given by Padre Richard Hall - Sunday 22 Apr 2012

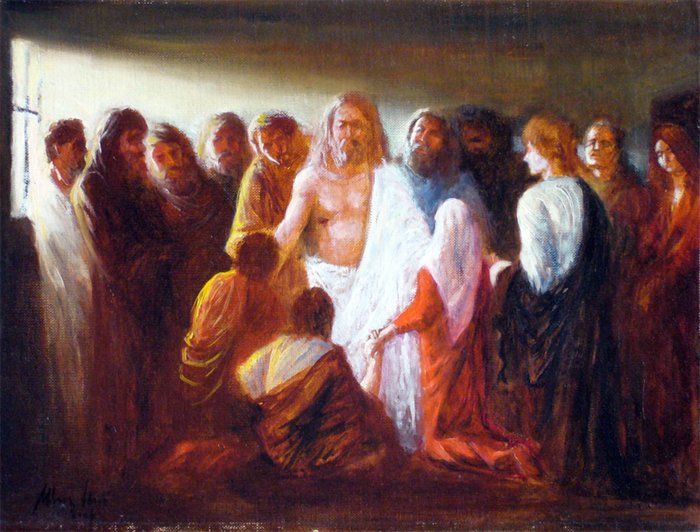

“Peace be with you.” The words of Jesus. “Peace be with you.” But what was the response of the disciples? “They were startled and terrified, and thought that they were seeing a ghost…. In their joy they were disbelieving and still wondering” Startled, terrified, disbelieving, wondering – some of the reactions of the disciples to the risen Christ. What is your reaction?

There was uncertainty amongst the disciples following their very first experiences of the resurrection. We perhaps have the advantage of hindsight. We have the advantage of the Church’s reflection of its Easter experience over nearly two thousand years. But still there is uncertainty, and still I’m sure perhaps for many of us there are difficult questions remaining. When we hear the Easter stories read in Church, when we read them ourselves, there is much to puzzle over, much that is difficult to understand. What is the resurrection? What exactly was the experience of the disciples on that first Easter day? Who was this Jesus, that, having been crucified, appeared to his followers, convincing them that he was alive? Who was this man, that appeared in rooms when the doors were locked and yet, as we heard in today’s Gospel reading, could eat food; who appeared to be physically present and yet who could instantly disappear from sight; who did not allow Mary to touch him in the garden and yet encouraged Thomas to do so. Who is this risen Jesus? Who is this man who says “Peace be with you”?

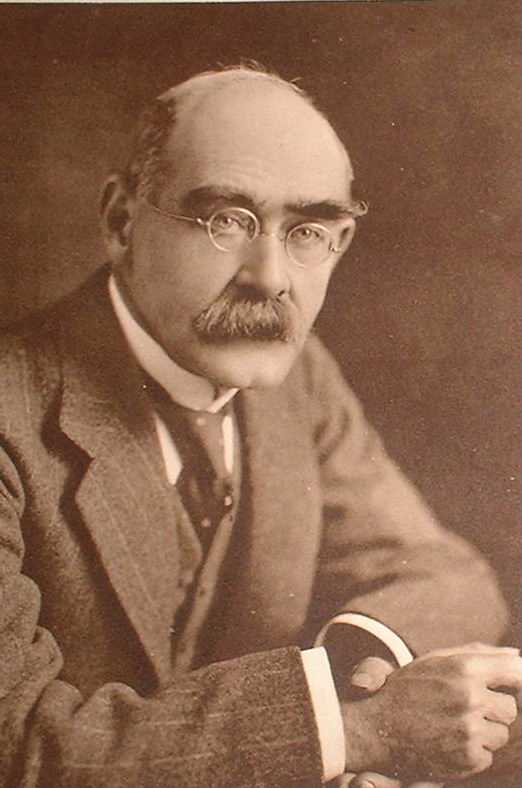

One of my favourite authors ever since childhood, perhaps through being a member of the Cub Scouts and being force-fed the Jungle Books, is Rudyard Kipling. Kipling is something of a controversial figure. He has been seen by some to have been a far too acquiescent observer of the British in India in the 1880s. He wrote indefensible things about Jews. He was rigidly conservative about the Boer War and Irish Home Rule. But he was by no means an out and out Western Imperialist: he was alert to British failings, and in his writing, he was often a good deal more respectful of Indian than of Western religion. Privately, he declared his disbelief in the Trinity and the doctrine of redemption. It seems likely that personal tragedy affected his religious views. Of his three children, two died young: his elder daughter at the age of six, and his son John, aged 18, on a battlefield in France in 1915. His son’s body was not located until long after Kipling’s own death, and after the war Kipling became a member of the Imperial War Graves Commission.

But Kipling’s faith must remain something of a mystery, given the nature of some of his writing. I’m going to read to you part of one of his short stories. It’s called “The Gardener”. It tells of an unmarried woman named Helen, who lovingly brings up a boy in a Hampshire village claiming that he is her nephew, the son of her brother and his wife who both died in India. (England, before the Great War, was not noted for its tolerance of illegitimacy and single mother-hood.) The boy enlists at the start of the war and is killed by a shell at Ypres. After the war Helen visits his cemetery, a place called Hagenzeele Third…

Next morning Helen walked alone to Hagenzeele Third. The place was still on the making, and stood some five or six feet above the metalled road, which it flanked for hundreds of yards. Culverts across a deep ditch served for entrances through the unfinished boundary wall. She climbed a few wooden-faced earthen steps and then met the entire crowded level of the thing in one held breath. She did not know that Hagenzeele Third counted 21,000 dead already. All she saw was a merciless sea of black crosses, bearing little strips of stamped tin at all angles across their faces. She could distinguish no order or arrangement in their mass; nothing but a waist-high wilderness as of weeds stricken dead, rushing at her. She went forward, moved to the left and the right hopelessly, wondering by what guidance she should ever come to her own. A great distance away there was a line of whiteness. It proved to be a block of some two or three hundred graves whose headstones had already been set, whose flowers were planted out, and whose new-sown grass showed green. Here she could see clear-cut letters at the ends of the rows, and, referring to her slip, realised that it was not here she must look.

A man knelt behind a line of headstones – evidently a gardener, for he was firming a young plant in the soft earth. She went towards him, her paper in her hand. He rose at her approach and without prelude of salutation asked: “Who are you looking for?”

“Lieutenant Michael Turrell – my nephew,” said Helen slowly and word for word, as she had many thousands of times in her life.

The man lifted his eyes and looked at her with infinite compassion before he turned from the fresh-sown grass toward the naked black crosses. “Come with me” he said “and I will show you where your son lies”.

When Helen left the Cemetery she turned for a last look. In the distance she saw the man bending over his young plants; and she went away, supposing him to be the gardener.

The imagery is obviously that of the resurrection appearance to Mary Magdalene in the garden. “Who are you looking for?” he asks. And she, having been shown her son’s grave, went away, “supposing him to be the gardener”. Helen is a woman much of whose life, though fulfilling has been based around a lie. She was living a lie. Though mentally and bodily whole, it was not until her encounter with the gardener that she gained the possibility of spiritual wholeness, the possibility of living life to the full, the possibility of peace. It is that wholeness, that fullness, and that peace that we are all called to by God. It is that release from ourselves that we are all offered by God. It is in that wholeness, that fullness, that peace, that we begin to experience eternal life. There is that of God in each one of us – it is evident from our capacity for compassion, our capacity for love. But we are human, and our capacity for love needs nurture – from ourselves, from each other, most of all from God. By seeking the risen Christ, by seeking the gardener, we will experience that nurture and we will grow towards that wholeness, that fullness of life, that peace that is the potential for all of us. Amen.