Sermon for Sunday 18th December

Sermon for Sunday 18th December

given by Revd Jan Kearton

Sometime between 1345 and 1434, Bianco da Siena wrote the great mystical hymn ‘Come down O love divine’, his plea to the Holy Spirit to come and make Bianco’s human life holy by its great and life-changing presence within him. He says, in Richard Littledale’s translation, ‘nor can we guess its grace, till we become the place wherein the Holy Spirit makes its dwelling’. It’s a plea that we’re used to hearing at baptism, at confirmation, and at ordination and, perhaps in a different way, at each Holy Communion.

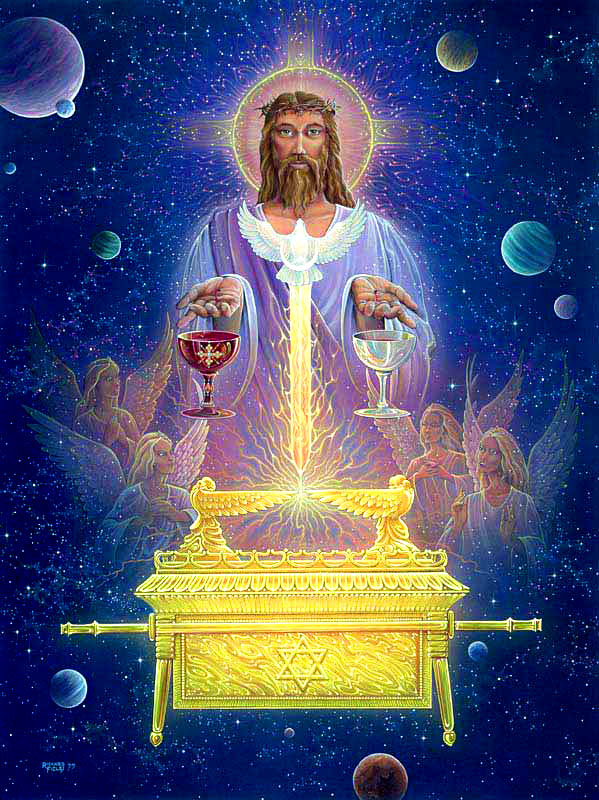

Throughout the Old Testament, God has consented to be with his people in the symbol of the Ark of the Covenant. It was a concession. God, wholly free and wholly powerful, chose to allow himself to be represented to his people and in some sense bound by the framework of the Ark. There’s a tension now between God’s freedom and God’s presence with his people.

In a period of peace, David is trying to establish his kingship and to make it secure. He’s built a city and wants to build a temple so that the people can know that God is with them exclusively and in a permanent way. Nathan the prophet is probably aware that David’s reasons are ambiguous - does he want his people to have a constant visual and ritual reminder of the God they serve, or is he trying to use God to make himself more credible and powerful? You can feel the tension rising. Nathan feels that the balance lies in building the temple anyway.

But God’s not happy. A permanent residence violates God’s freedom and a fixed place overturns the idea of God’s coming and going amongst all his people, which the Ark maintained. God points out that it’s his actions which have brought about David’s kingship. God chose him when he was a shepherd, God went about with him and shaped the victories that David enjoyed, God brought Israel to the place where David has built a city and it’s God whose given the relief of the rest that they are all experiencing. God reminds David that he, God, is greater than any plans that David might have for him.

Throughout the Old Testament the people have lived in a conditional covenant relationship with God where God has said ‘I will be your God if you ...’ But at the precise moment that David’s being reminded who’s boss, a most extraordinary thing happens. David has wanted to establish a house for God, and God now turns the tables on David and establishes a house, a lineage, for David. God makes a new covenant with David, and it’s unconditional.

Regardless of what happens, David’s ‘house’, his line, will exist for ever. The ‘house‘ of David will be in a special relationship with God and God will be very closely associated with David’s line for ever. It’s as if the holiness of God will in some way come to dwell in David’s line of descent permanently. David has been blessed with extraordinary grace as his line becomes the place that God chooses to ‘dwell’, to be part of. He and his descendants will be justified by the same grace - there may be sanctions and punishments, but they won’t ever be terminal because God is busy shaping history through it.

This new thinking sets up a longing for the Israelite peoples, and it sets up a longing. At some point, the line of David will produce a person who’ll right wrongs and rule well. It’s the beginning of messianic hope. It turns Israel into a community that’s held together by the hope it bears. The strange thing is that God does all this in spite of the tension between what’s right for David and his purposes and what’s right for God and God’s purposes. Faith, promise and hope stand side by side with David’s political interests and it looks as though faith can be close to the realities of political life.

But doesn’t that leave a gap? Doesn’t it allow faith to be misused ideologically? Well yes, it does. We can all cite plenty of times in history and our own time when faith has been misused. God balances that risk with the need to lead a people whose faith makes a difference in the world rather than a people who’s faith is pure and unworldly. God calls his people to work out their faith in the world and find their way through its tensions, even if they make huge mistakes. The conditional covenant still exists and the people of God have to struggle with the ‘if’ word and try to be the people that God calls them to be - but they have the reassurance that, in the particular case of David’s line, the hope of rescue is for ever.

Let’s pan the camera forward a few centuries. Mary now enters the spotlight. She’s engaged to a man who’s part of the line of David and she’s a holder of the messianic hope of Israel, one of those who pray for the coming of messiah. The angel tells her that ‘the Lord is with you’. Mary, very sensibly, wonders what’s going on as that greeting would tell her that God’s company will be a mixed blessing, that there’s hard work to do. She is, to use da Siena’s language, to become the place wherein the Holy Spirit will make its dwelling. If she will agree, Mary will bear in her body the hope that Israel has carried, the fulfillment of the unconditional covenant with David.

Mary consents, thanks be to God. ‘Let it be.’ Three small words that change the course of human history and give hope to the whole of creation. Costly hope though. Any agreement to be part of the work of God is usually costly, especially when it has to do with re-making a broken world. John Pridmore reminds us of a modern myth that demonstrates the costliness - Frodo consents to become the bearer of the ring and so he also becomes the place where the hope of Middle Earth is vested, hope that Mordor will be destroyed and a time of healing, peace and joy can begin.

The poet Denise Levertov believes that annunciations happen in most people’s lives. ‘Roads of light open’ she says, but we turn away. Sometimes it’s dread that prevents us from taking the risk, sometimes it’s weakness or despair, sometimes it’s the simple relief of turning from God’s gaze and demand. Life goes on, but a gate has closed. God has come to possess us and we have the power to consent or refuse. Simone Weil says that, if we refuse to hear, God comes again and again like a beggar but that, like a beggar, one day he will stop coming to ask.

The hope of the unconditional covenant is for ever, and at Christmas Jesus comes into the world. In him, the conditional covenant will be made unconditional for all God’s people, not just those of the line of David. The final piece of our preparation for his coming has become clear. We’re to look and listen to the annunciation that may be happening in our lives. Where is God asking us to consent to becoming part of his shaping of the world? What fears and uncertainties are preventing us from hearing, what weakness and despair keeps God out, and when can we confess to have felt relief from turning aside from his requests?

Is there any part of our life where we, like Mary, can say to God ‘let it be so’? Can we become afresh ‘the place wherein the Holy Spirit makes its dwelling’? In this final week before Christmas, in the midst of the hustle and bustle of the world, each of us is called to renew the cradle of our hearts to receive the Christchild. May Christ open a road of light for each of us as he comes ever closer to us. AMEN.