Sunday sermon for 11th September 2011

Sunday sermon for 11th September 2011

(Scroll to bottom for a list of other past sermons)

Sermon given by the Revd Jan Kearton

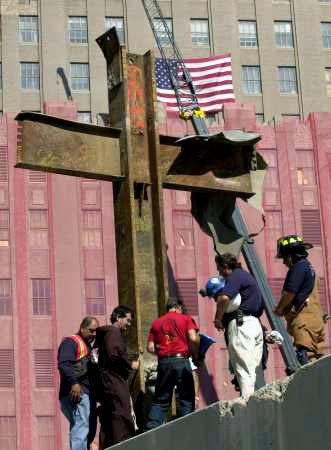

It can’t have escaped anyone’s notice that today is the 10th anniversary of the terrorist attack on the twin towers in New York and the Pentagon in Washington, and the downing of Flight 93 in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Those events killed 2977 victims and 19 perpetrators also died. The attacks provoked the War on Terror, the invasion of Afghanistan, countless attacks on Muslim, Sikh and other non-white people living in western countries. Four years later on the 7th July 2005, 52 people died in the London bombings together with the 4 bombers. It isn’t easy to remember these events because to remember is to continue to feel vulnerable in the face of such horror, but those events have continued to challenge our opinions, beliefs and behavior ever since.

How have we been led to think about the effects of such events as 9/11, 7/11 and the continuing war on terror? Governments and the media have talked about sacrifice, patriotism and nationhood. Terrorists sacrifice their victims for a cause, brave people sacrifice their lives to help others or to stop similar future events. Patriotism talks about what a good and loyal citizen's response should be according to the opinion of media editors and government ministers. Nationhood asks what it means to be American or British or Arab or whatever race after such events.

I have a friend who is a research scientist and lecturer in psychology in a large UK research university, a post she’s held for more than thirty years. My friend has lots of friends around the world from many different cultures. When I asked her what effect the London bombings have had on her, she told me that earlier this year a young Arab man came to sit next to her on the tube, holding a large rucksack. She was unable to quell her panic and got off at the next stop. My friend knows better than most that Islam is not a violent religion. She knows that responses driven by suspicion and fear are irrational and unfair and can lead to serious misjudgments. She felt ashamed at her reaction but she knew that it was visceral and she hadn’t been able to change it.

Asked last week how he thought about 9/11, 7/11 and the war on terror, the Prime Minister said that the world was now a safer place. Why is it then that it doesn’t feel safer?

The voices of the media and politicians are very different from the voices of those in New York who’ve been affected. Columbia University conducted careful interviews with New Yorkers affected by their experiences, and these have now been published. A poet living in America says that she has felt a deep sense of guilt that she can’t really place or understand, guilt that stopped her writing poetry for two years. She experienced a shift in identity. Previously, she’d thought about herself as an Afghani woman living in America. Now, she refers to herself as Afghan American, a shift in identity that respects her cultural origin but better defines her sense of being alongside her fellow Americans.

A disabled Pakistani man, Zaheer Jaffrey, was on the 70th floor of one of the towers when the plane struck. His son said that he feared that his father might be dead as it would have been so difficult for him to get down a staircase. His father managed to make his way out of the building and to leave the area before it collapsed. Later, they reflected on their experiences. The son said that his great fear for his father was less than his terror now of living in a Moslem immigrant community after 9/11. His father said that he’d had worse experiences in war than being in the tower, and that the worst thing of all was to see his son unable to leave the boundaries of his Moslem community because he was so afraid of reprisals.

There are stories that are missing completely - of those who won’t be remembered because their relatives have suppressed them - illegal immigrants in the twin towers whose families daren’t speak about them because their own situations will be exposed. There are stories from those who rushed to help, difficult, complex stories from fire crews about leaving people behind in order to save themselves when the towers collapsed. Each story tells of the profound and different changes that have happened to people as a result of their experience.

Take Jimmy Dobson, an emergency medical technician who survived in appalling circumstances and continued to ferry other survivors to medical stations. He’s angry with the American government, the Port authority and the American public. He feels that the work of medical technicians has been completely overlooked whilst the stories of firefighters and steel workers dominate. Apart from a primary school class in a remote part of America, no-one has yet said thank-you to him. But here’s what he says about the changes that have happened to him:

‘Yes, it’s changed. It’s changed. The one thing that’s changed the most is, like, what’s going on in Afghanistan. Even after this happened and they started talking about retaliation, I’m more of a pacifist than ever. I’m a Republican - but what I saw that day, the devastation, I could not see us doing that to other people. Life is too cheap then; it doesn’t mean anything and there’s no reason for it.’

In Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus is speaking about forgiveness within the Church community and it is a bit of a leap to apply his thinking to terrorist offences, but his principals are grounded in what he knows and experiences of the nature of God his Father. Forgiveness is difficult for all of us when the offences against us are intentional and repeated. Peter asks how often he should forgive - it’s a fair question because either there have to be limits to our patience with bad behavior, or wrong doesn’t matter. How does Jesus seem to think about forgiveness? He speaks about it as the polar opposite of revenge. Lamech in Genesis proudly says he’ll avenge himself seventy-sevenfold on anyone who dares to attack him, but Jesus tells Peter to forgive not seven times but seventy seven times. Christians who want to be part of the kingdom of heaven must give up the human desire for revenge, even when they’re repeatedly hurt.

Jesus then tells the parable of the man who embezzled tax revenue that’s the equivalent of the daily wages of 100 million laborers - a huge amount which he would be deluded to think he could ever repay. Yet the king turns from his threatened punishment and forgives the man the whole of his outrageous debt. In his turn, the pardoned embezzler treats a man with a small debt to him harshly and earns the king’s real and lasting wrath in return.

Can we imitate God by being lavish with our own forgiveness? Can we write off the events of 9/11 and 7/11? Probably not. We can’t become as perfect as God just by imitation. But God will, if we depend upon him totally as his children, help us to show something of his own forgiveness to those who sin against us. Resisting the human temptation to get even is only possible through fervent prayer for the grace to reflect God’s own generosity.

Harsh condemnation of others doesn’t help us to see what we have contributed to the problem: premature forgiveness is a form of cheap grace that avoids dealing with the issues that divide us. Hurt and fear do matter. The king’s forgiveness in the parable wasn’t given until after he had investigated what was wrong. Neither condemnation nor cheap grace help those who offend and they can’t mend broken relationships. Jesus’ methods are to challenge offences by dialogue not by vindictiveness. Jaw, jaw, jaw as Churchill said, is better than war, war, war. We must continue to work on our forgiveness and Islam must continue to ask itself what it is in its own practices that supports terrorism. We must continue to ask how our self-understanding and practices in the western world exclude and denigrate others. Forgiveness will come when we better understand each other true relationships can be established.

I leave you to reflect on whether you think 9/11 and 7/11 would have happened if we in the west were prepared to release our grip on both power and the global commodity markets. I urge you to reflect on whether you believe the war on terror has made the world a safer place or whether it’s created new terrorists in place of those killed or detained; whether the war in Afghanistan was motivated by fear, revenge or sheer necessity, by a concern for the safety of citizens or a concern for their votes.

Whatever your conclusions, let us all honour this anniversary by praying fervently for grace for three things: to know our own faults, limitations and blindness; to long for dialogue more we long for than revenge; and to depend on God so completely that we understand ourselves as massively in debt to God yet forgiven. Perhaps then we will be able to forgive others the debts they owe us and live as those who, however dimly, reflect God’s generous and loving forgiveness to us and to others. AMEN.